Kerby Jean-Raymond

A Designer, and a Collection, Inspired by an Immigrant Father

For those who want their fashion designers to be both creative and political, Kerby Jean-Raymond is a case study.

The designer, who turned 30 last year, and founded his label in 2013, first made waves with his spring 2016 show, which featured a short film about race relations in the United States. Since then, he has designed T-shirts that listed the names of victims of police brutality; traveled to North Dakota with supplies for the Dakota Access Pipeline protesters; and created a collection that explored the theme of economic inequality.

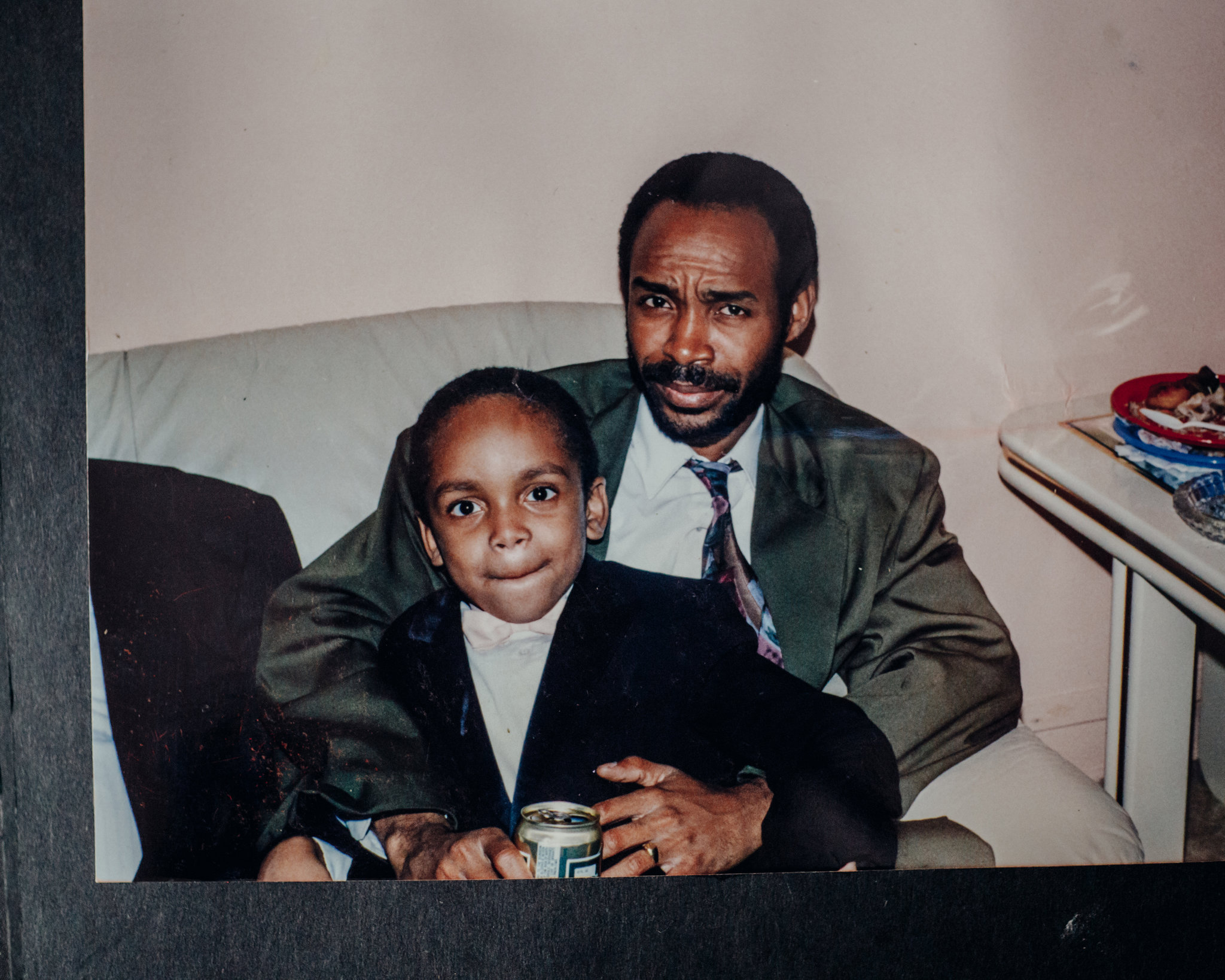

This season, Mr. Jean-Raymond drew inspiration from his father, Jean-Claude Jean-Raymond, 59, who arrived in New York from Haiti in 1980 and who raised Kerby alone after his wife, Vania Moss-Pierre (Pyer Moss is her namesake), died when his son was seven. The collection is titled “My Father as I Remember, 1980-1999,” and is the first part of a multiseason series called “Stories About My Parents.”“My dad was always so strict that I was scared to speak to him,” Mr. Jean-Raymond said recently, driving through East Flatbush, Brooklyn, where he grew up. “Haitian parents are very, ‘This is adults’ business; this is kids’ business.’”

At the apartment where his father has lived since 1982, Mr. Jean-Raymond scrolled through his phone as Jean-Claude Jean-Raymond looked on. “He randomly sent me these pictures on WhatsApp a few months ago and I started designing my collection around them,” Mr. Jean-Raymond said, scrolling through the messaging app. “It’s an ode to the cars that he drove, the excessive amount of jewelry he wore.”

“I grew up in a different Flatbush,” Mr. Jean-Raymond added. “When we went outside for recess there would be drug dealers in the yard. We used to take milk crates and hang them on the fence to play basketball.” His father said, “There was an area nearby called Vietnam,” referring to a stretch of several blocks near Flatbush Avenue. “Day or night, you couldn’t walk in this area. It was too dangerous. But the same area now, there’s a Starbucks.”

“I never sold drugs,” Kerby Jean-Raymond said. “There were times when gangs would approach me, but my father was way stronger than them. They would come make threats and stuff, and I was like: ‘You don’t know the opposition I’ve got upstairs. I’m not scared of you.’”

He did, however, have a lifelong obsession with sneakers, financed starting when he was 13 by an after-school job at a sneaker store on Flatbush Avenue called Ragga Muffin (he told the hiring manager that he was 15). “The way I was raised, you get a new pair of sneakers when the old one gets messed up,” Mr. Jean-Raymond said. “But when I got to high school, I started dating girls and trying to fit in, and I realized everybody was collecting Jordans. When I would get my paychecks, I wouldn’t even take money. I would just trade them for sneakers.”

“It’s completely different,” he said of today’s Ragga Muffin. Still, he credited the place with inspiring his career path. Seeing the less-than-high-quality pieces that sold while he worked there, he thought to himself: “I can make something better.” Mr. Jean-Raymond had always been an impatient, antsy child, and to channel his energy, his homeroom teacher at the High School of Fashion Industries in Manhattan had him work as an intern with the designer Kay Unger, who became a mentor.

Though he attended Hofstra University and earned a degree in business law and entrepreneurship, he continued to freelance for Marc Jacobs, Theory, Kenneth Cole and others, helping with showroom preparation, draping and pattern making. Then came Pyer Moss, now based in Manhattan’s garment district. Back at the office, Mr. Jean-Raymond went over several pieces-in-progress with his team. “I’m taking classic cuts, but I’m doing them in textures that remind me of him,” he said, referring to his father. A bright silver, furry jacket lay on a table. Nearby was a sleek tracksuit in black and purple, and a large leather jacket purposely left unfinished. Also part of the collection: a hand-drawn patch featuring an image of his father in his youth with his nickname, “Didi,” printed below.

He picked up a dark burgundy and black coat, inspired by a Maison Margiela style his father wore when Mr. Jean-Raymond was a child, and put it on. Maison Magiela and Yohji Yamamoto are the only two labels Mr. Jean-Raymond now wears besides his own. “It was the first time I saw the word Margiela,” he said of the original piece. “I could tell you exactly what he would wear it with. A cream suit and a Van Heusen shirt and brown corduroy pants.” He did not love the look, back in the day. “Now, I think that’s fly.”

After wrapping up at his studio, Mr. Jean-Raymond headed to Le Soleil Restaurant on 10th Avenue for lunch.The Haitian restaurant is owned by his uncle, Alphonse Duval, and his aunt, Rolande Bissereth, who is also Mr. Jean-Raymond’s godmother. What his father did not provide in emotional connection she provided in spades, he said. He spent weekends with her at her home in Queens and at the restaurant, working behind the counter, cleaning up and serving food. “If she was here now, I wouldn’t be sitting,” he said.Mr. Jean-Raymond ordered a selection of Haitian dishes: plantains, fried goat with onions, conch, rice and beans, deep-fried accra (a root vegetable) and a side of spicy chili sauce. One of his future collections in the “Stories About My Parents” series will be about his godmother and his mother.

For now, Mr. Jean-Raymond is still focused on unraveling the complex relationship he has with his father. “We’ve never had an

open line of communication,” he said. “I hope this shows him that I’ve cared the whole time. I just didn’t say anything.”